In a simple democratic election with two candidates, every voter has the same probability of affecting the result of the election. In the United States, the electoral college ensures that this is not the case. Instead, the chance that your vote matters is dependent on which state you live in, and the political composition of voters who happen to live within that state's borders.

Although Republican presidential candidates have benefited from the electoral college in recent years—2 of their last 3 election winners lost the popular vote—there is nothing about the electoral college that specifically favors Republicans. Its effects are largely random, and can be expected to change over time. One illustration of how arbitrary these effects are is that a state's status as a swing state can often be eliminated by moving a few counties into a bordering state, instantly devaluing the value of its residents' votes. It would only take a couple of these changes to shift the advantage of the electoral college to the Democratic party.

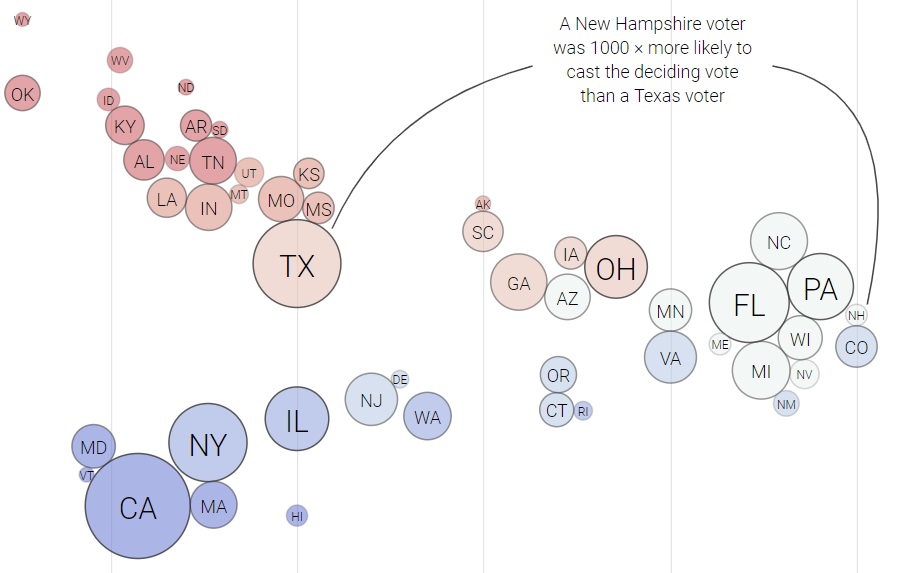

For 2016, researchers Pierre-Antoine Kremp and Andrew Gelman used polling data to estimate the probability of casting the decisive vote for voters in every state. This measure of how your vote matters, plotted below, highlights the main feature of the electoral college: Some people's votes matter and some simply don't. Note that the scale used below is logarithmic: Doubling the space between two states actually represents a ten-fold increase in the difference in voter power.

Color = 2016 vote share (Dem - Even - GOP)

Data: Pierre-Antoine Kremp and Andrew Gelman, American Community Survey 2012-2016, Wikipedia

In terms of vote power, the median voter lived in Illinois or Texas in 2016. Voters in New Hampshire and Colorado were 1000x more likely to affect the election results than the median voter. Voters in Nevada, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania had 500x as much power as the median voter. Voters with the least power lived in the solidly Republican states of Wyoming and Oklahoma, with 1/30th the power of the median voter, and 1/30,000th the power of voters in New Hampshire and Colorado.

Arguments about the merits of the electoral college often turn to how it affects certain categories of voters. Proponents of the electoral college sometimes argue that voters in cities should have less power than voters in rural areas. Opponents of the system argue that it privileges white voters over minorities. But are these thing true?

If we consider voters who live in states with 100x the power of the median voter to be "high-power voters,"" we can simply calculate the percentage of high-power voters in each demographic group across the country. Overall, these people make up 27.7% of the citizen voting-age population.

The incidence of high-power voters is highest (29.6%) among white non-Hispanics, and slightly less among black non-Hispanics (27.1%). Those disadvantaged by the electoral college are Hispanics (21.8%) and those who fall into other racial categories (19.0%). The disadvantage to Hispanic voters is likely due to the high percentage of Hispanics in non-swing states of Texas and California. This could change if Texas were to become a swing state, as some predict.

Breaking out the civilian voting-age population by census tract density tests the hypothesis that the electoral college reduces the voting power of urban voters. Here I am using the density cutoffs used by Jed Kolko here, as well as an additional cutoff for suburban tracts used by David Montgomery's Congressional Density Index. This reveals that only 21.9% of voters in urban areas are high-powered voters. So it is true—at least for the moment—that the electoral college puts urban voters at a disadvantage.

As noted earlier, a lot of this is very tentative, and is based on which states happened to be split most evenly in 2016. Which states will have the most powerful voters is subject to change, and there's not really anything meaningful driving those changes. It's mostly just a matter of the combinations of voters that happen to fall within state borders on election day.

Note: Source code for calculations and tabulations can be found here.